Project Information // Project Advisors // Incorrigibles Team // Press

What We Do

Incorrigibles is a transmedia project that tells the stories of ‘incorrigible’ girls in the United States over the last 100 years—beginning with New York State. We draw on the personal narratives of young women in “the system” to investigate the history and present state of youth justice and social services for girls.

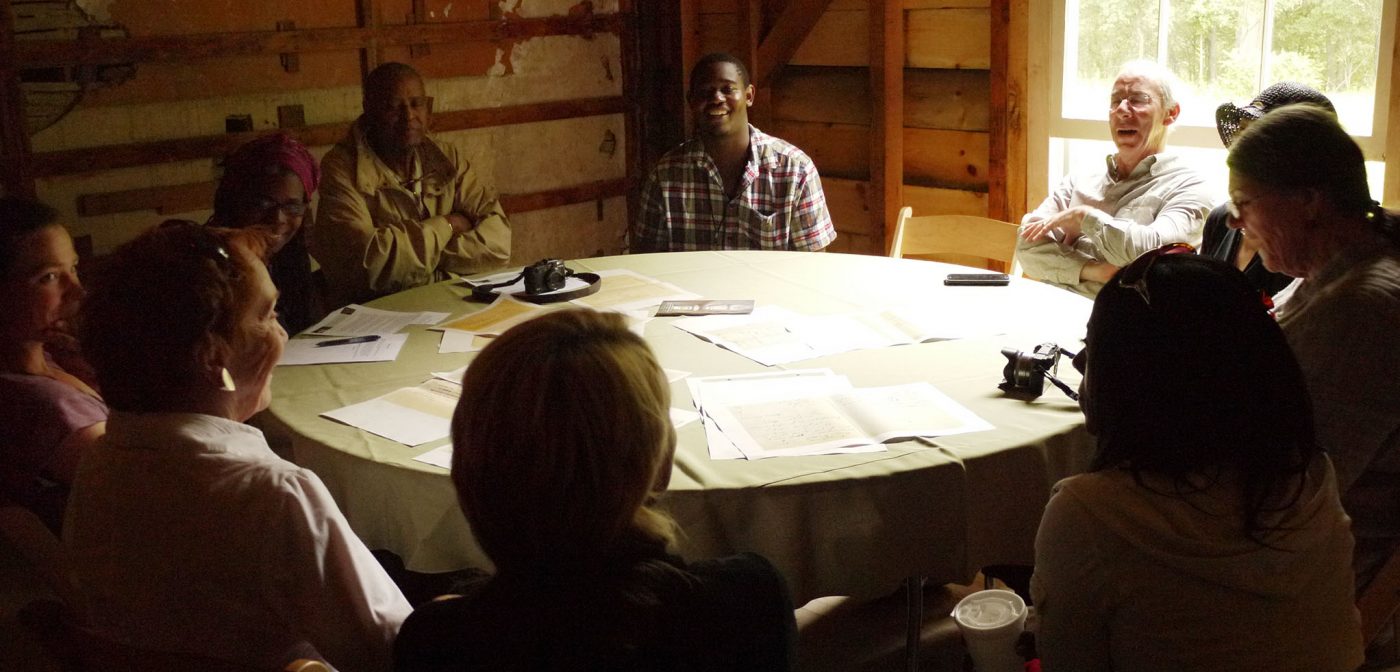

Our current project centers on gleaning information from archival documents from the New York State Training School for Girls (1904-1975), but we are expanding our research to include all youth detention centers in the United States; recording and sharing accounts of women alive today who were confined in these institutions; and organizing community engagement events with young women and the public to encourage critical analysis around youth detention and behavioral intervention.

A Note from the Director

‘Incorrigible’ is a term I encountered again and again while studying various source documents, including records from the New York State Archives and The New York Training School for Girls in Hudson, New York—the project’s’ pilot site of study. The term was used to describe and categorize the young girls (ages 12-18) who were incarcerated there.

The term expressed to me how they were perceived and labeled by the people around them as “unable to be corrected or reformed.” Digging through documents and historical images spanning the period between 1904 and 1975, I have discovered letters that the young women at the Training School wrote to their families, detailed reports of doctor’s examinations, legal decisions made by the court that led to their incarceration, and letters written by parents to the institution. One of the young women deemed ‘incorrigible’ and incarcerated at the Training School during the 1930s was the legendary jazz singer, Ella Fitzgerald.

Today, scientific research into the neuroplasticity of the brain makes a strong case for the argument that incorrigibility “is a term inconsistent with youth.” This view was further validated in 2012 by a ruling by the Supreme Court.

The Training School’s history holds significant meaning for contemporary debates around penal reform, child welfare, juvenile justice, use of solitary confinement, and the role that race, gender, income, and immigrant status play in determining what is a crime and what kind of punishment is appropriate. “..we got sent to isolation. And isolation for me was horrible. They had the lights on. You were in a locked up room. The walls were padded. I was told the next time I got in trouble it wouldn’t be reformatory school. It would be jail,” says Sharon Anderson, now in her fifties. Liz Stenson, a passionate woman in her early sixties recounts, “We were there because nobody wanted us, so our common bond was we felt rejected. I ran away from Hudson Training School four times.” Liz was eight-years-old when she was sent away to a foster home and twelve-years-old when she was sent to the Training School.

Inspired by the stories of these women, a trove of archival evidence from the Training School, and in-depth contextual research, Incorrigibles is a work that sets out to make visible the deep patterns, both linguistic and penal, that have laced not only our own perception but also the strategies to deal with what North American society has perceived as threatening and disruptive in the behavior of some young women, then and now.

Given the recent Gender Injustice Report, The Girlhood Interrupted Report, the Abuse to Prison Pipeline Report issued by the Human Rights Project for Girls, the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality, and the Ms. Foundation for Women, this project is all the more timely.

-Alison Cornyn